Blues is the root of almost all modern music and has produced countless legendary tracks that became immortal on six strings and 88 keys. In this article, we present 10 unforgettable blues and blues‑rock songs every musician should know.

Founder and Piano teacher

Imagine your fingers gliding effortlessly across the piano keys. Every melody you play sounds smooth and confident. You improvise freely and express exactly what you feel. Sounds like a dream? The key is simpler than you think: piano scales.

In this guide, we’ll take you step by step through everything you need to know as a beginner about piano scales, and how the right exercises will not only improve your technique but also help you understand the language of music from the ground up.

Table of contents

A piano scale is a sequence of notes arranged by pitch. They are made up of a series of whole and half steps and form the foundation of melodies and harmonies. In addition to the most important scales (major and minor scales), there are many others, such as the chromatic scale or the pentatonic scale. Practising scales is crucial for developing finger dexterity and for gaining a solid understanding of musical relationships.

You could say: notes are the letters of music, and scales are the words. They give every piece of music its structure, its colour, and its emotional depth. Whether a song sounds joyful, sad, tense, or mysterious depends largely on the underlying scale.

For you as a pianist, piano scales are far more than just a technical finger exercise. They are your personal gym for the hands and your compass on the keyboard. By practising them, something magical happens:

Your fingers become faster: you develop muscle memory and clean technique.

Your playing becomes smoother: transitions between notes become graceful and fluid.

You understand music theory: you intuitively learn keys, chords, and harmonies.

You can improvise: knowing which notes work together allows you to create your own melodies.

You can transpose: shifting notes by a set interval or moving an entire piece into another key.

In short: mastering piano scales means you don’t just play notes – you make music.

Imagine sitting at the piano, your fingers gliding effortlessly across the keys as you play melodies that move your heart. With music2me, you can learn piano at your own pace – step by step with a system that truly helps you progress, whether you’re a beginner or already advanced.

Over 400 video lessons & downloadable sheet music

Interactive tools like Skill Check & smart practice mode

Weekly live classes & personal teacher support

Exclusive Discord community for motivation & exchange

The world of scales is vast, but don’t worry: you don’t need to know them all at once. For a successful start, we’ll focus on the absolute basics, which already allow you to play countless songs.

The C major scale is the classic choice for every beginner. Why? It consists entirely of white keys.

C major scale: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

Basic structure of the major scale: whole – whole – half – whole – whole – whole – halflb

It is, so to speak, the “home” of music – completely pure, clear, and free of accidentals. This key gives beginners an initial sense of musical order and spatial orientation on the keyboard. Here you can fully concentrate on correct finger movement and an even touch without having to deal with black keys.

Next come other major keys, such as G major (with one sharp, F♯) and F major (with one flat, B♭), which introduce more accidentals. These two keys broaden your horizon and challenge your fingers a little more, while still remaining manageable. You can read more about this in our article on learning the major scale.

The natural A minor scale uses exactly the same notes as C major but starts on A. It is the so-called relative minor and sounds more thoughtful and melancholic.

A minor scale: A – B – C – D – E – F – G – A

Basic structure of the minor scale: whole – half – whole – whole – half – whole – whole

With these two types of piano scales, you can already discover and create a wide spectrum of music, and you will immediately feel the emotional difference a key can make. If you want to develop your skills further, our article on the minor scale shows you how to form typical chords and make effective use of its melancholic mood.

The secret to learning piano scales is not working for hours on end, but practising cleverly and regularly. To learn scales effectively, it helps to vary your exercises and focus on different aspects of playing. Here are some exercises that will help you not only play scales mechanically, but also develop a deeper musical understanding and greater finger dexterity.

Your best friend when practising is a metronome. Begin at a very slow tempo. The goal is not speed, but absolute clarity. Every note must sound clean and even. Only when the scale is perfect at a slow tempo should you gradually increase the speed.

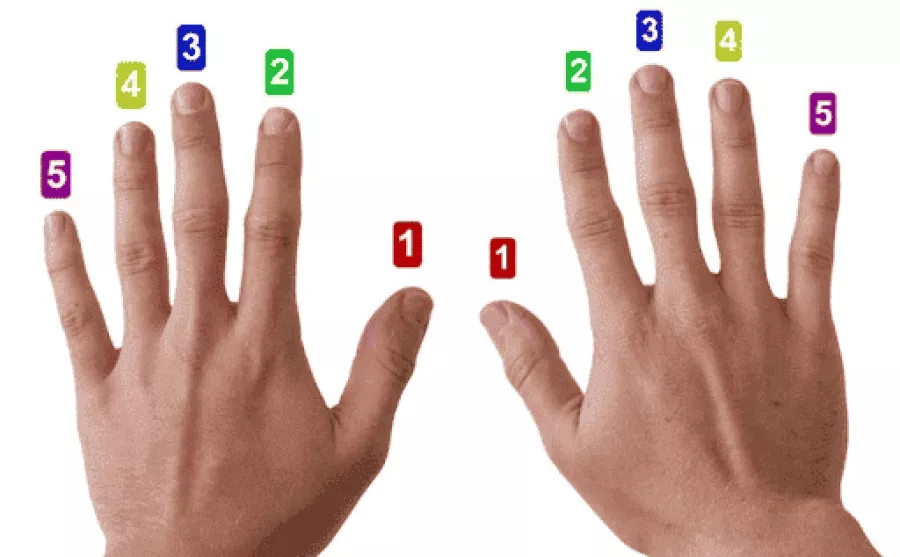

Proper fingering is the key to smooth and relaxed playing. It has been refined over centuries so that your hand can glide effortlessly across the keys. The standard formula: the fingerings for major and minor piano scales follow a clear logic that you learn once and then apply consistently.

Right hand (ascending): 1-2-3, 1-2-3-4, (5)

Left hand (ascending): 5-4-3-2-1, 3-2-1

The thumb rule: as a general rule, the thumb (finger 1) usually does not play black keys. It slips cleverly under the other fingers (thumb-under technique) to keep the movement smooth.

Don’t overwhelm yourself. Practise first with your right hand until the sequence feels secure. Then practise with your left hand. Only when both hands can play the scale confidently on their own should you slowly put them together.

Practise the scale not only ascending but also descending. Start on the highest note and play back down. To make the exercise more challenging, vary the tempo: play upwards slowly and downwards quickly – or the other way round.

Refine your technique by practising piano scales with different articulations. These exercises give you maximum control over your touch and increase the flexibility of your fingers.

Legato: smooth and connected, with no audible gap between notes.

Staccato: short and detached, as if the keys were hot.

Instead of moving from one note to the next, play the scale in leaps. For example, play a third (skip two notes) or a fourth (skip three notes) upwards from each note. This challenges your ear and finger dexterity and helps you understand chord structures more clearly.

A fantastic exercise for improving finger coordination is playing double notes. Play two notes of the scale simultaneously, for example with your thumb and little finger. This sharpens your ability to control multiple voices at the same time.

Don’t just play the notes mechanically – listen to them carefully. Try to sing the scale, either inwardly or out loud, before playing. This way you develop a much deeper connection to the music, train your ear, and make your playing more expressive.

The best way to truly master a scale is to use it creatively! Try inventing short, simple melodies with the notes of the scale you’ve just learned. This way you internalise it as a musical tool rather than just a dry exercise.

Consistency is key. Set fixed but short practice sessions. Most importantly: celebrate your small successes! Be proud of every scale that sounds cleaner than it did yesterday. A positive and patient attitude towards yourself is the best engine for long-term motivation and progress.

You’ve mastered the major and minor piano scales and feel curious for more? Perfect! The world of music is even bigger and more colourful. The following scales are like spices that add a special flavour to your melodies and improvisations. Let’s take a look beyond the basics!

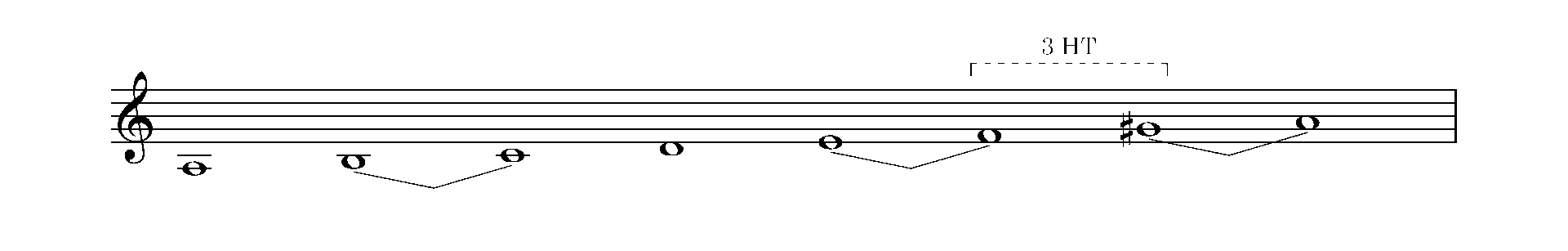

The harmonic minor scale is almost identical to the natural minor, but with a dramatic twist at the end: the seventh note (the leading tone) is raised by a semitone. This small change has a huge impact! The raised seventh creates strong tension that naturally resolves back to the tonic – musicians call this a strong leading tone. That’s why this scale often sounds mysterious, oriental, or dramatic. It’s a favourite tool in classical music and film scores for building tension.

Structure: Like the natural minor, but with a raised 7th degree.

Example in A minor: A – B – C – D – E – F – G♯ – A

The melodic minor scale is a clever blend of minor and major. Its special feature: it sounds different ascending than descending. On the way up, both the sixth and seventh notes are raised. This makes it smoother and more flowing than the harmonic minor and closer to the sound of major. On the way down, the raised notes are lowered again, so it matches the natural minor scale. This elegant movement makes it especially popular for ascending melodies.

Structure (ascending): Natural minor with raised 6th and 7th degrees.

Example in A minor (ascending): A – B – C – D – E – F♯ – G♯ – A

Example in A minor (descending): A – G – F – E – D – C – B – A

The chromatic scale is the most complete scale of all. It makes no distinction between keys, as it contains all 12 notes of the Western tonal system, each a semitone apart. On the piano, this simply means playing every white and black key in order.

Structure: 12 consecutive semitones.

Example starting from C: C – C♯ – D – D♯ – E – F – F♯ – G – G♯ – A – A♯ – B – C

It’s less of a foundation for melodies and more of a musical colour palette – as well as a fantastic exercise for finger dexterity. In jazz, rock, and film music, it’s often used for fast runs or as a transition between chords.

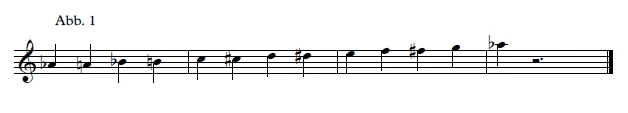

The pentatonic scale is one of the most popular and easiest piano scales to play. Its secret: it consists of only five notes per octave. It leaves out exactly those notes that could cause dissonance. The result? You can play almost anything – and it nearly always sounds good! That’s why it’s the perfect scale for your first improvisations.

Character / Sound | Derived from … | Omitted degrees | Example notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Major pentatonic | cheerful, open | major scale | 4th and 7th degrees | C – D – E – G – A |

Minor pentatonic | bluesy, melancholic | natural minor scale | 2nd and 6th degrees | A – C – D – E – G |

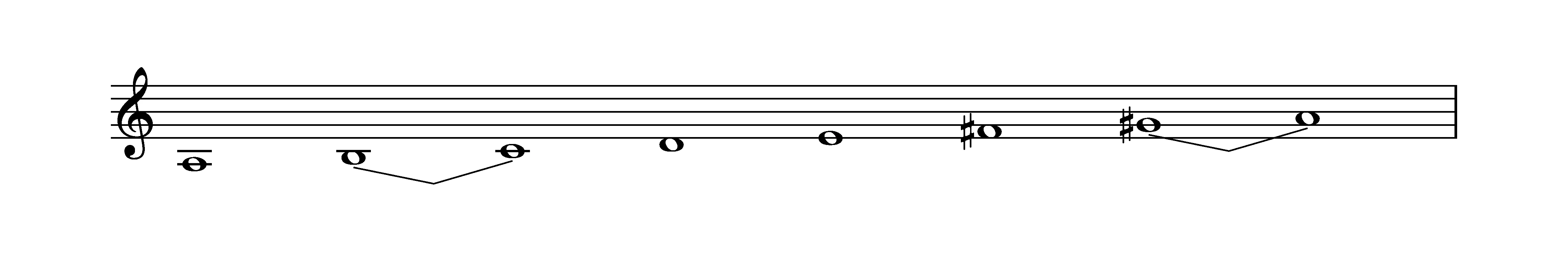

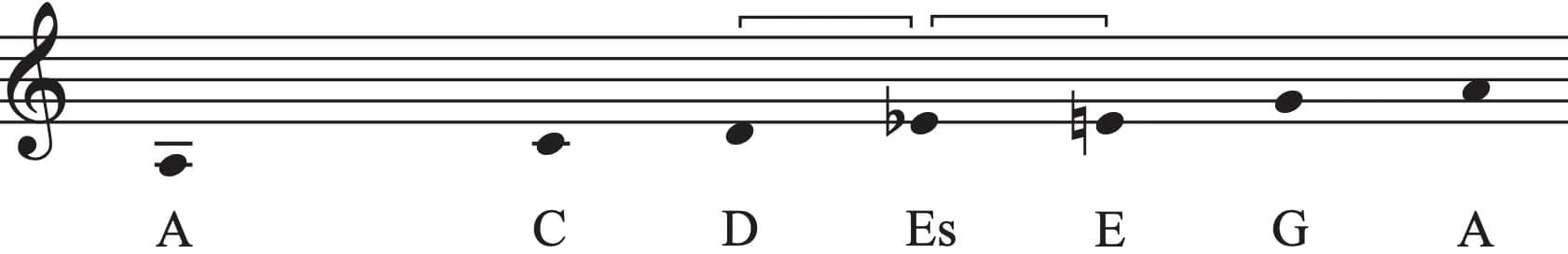

The blues scale is the very core of countless solos in blues, jazz, and rock. Essentially, it’s a minor pentatonic with one single but crucial addition: the “blue note”. This blue note is a diminished fifth and gives the scale its typically plaintive, edgy, and incredibly soulful sound. It captures the very soul and longing of the blues perfectly.

Structure: Minor pentatonic plus a diminished fifth (the “blue note”).

Example in A: A – C – D – D♯ – E – G – A

The church modes (also called modes) are the ancestors of today’s major and minor piano scales. There are seven different modes, all based on the major scale but starting on different degrees. As a result, each mode has its own unique colour and mood – from bright and floating (Lydian) to dark and mysterious (Dorian). They were the foundation of many ancient chants but are also making a comeback in modern music such as jazz, folk, and film scores to create special atmospheres.

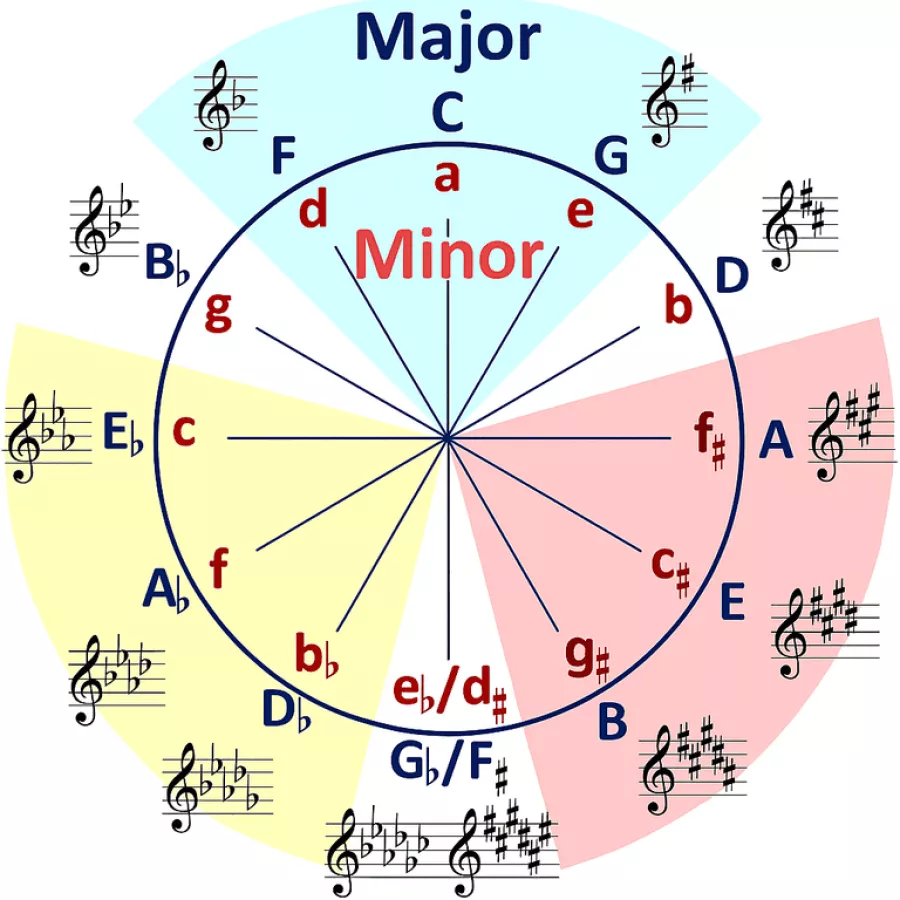

Do you wonder how to remember all the piano scales with their different accidentals (♯ and ♭)?

The answer is: the circle of fifths. It is a graphical representation that shows you at a glance:

Which key has how many accidentals.

Which major and minor keys are directly related.

The circle of fifths is the ultimate tool for understanding the relationships within the harmonic system and makes life much easier for any musician.

Piano scales are not a necessary evil but your personal gym for the fingers and the key to musical freedom. They form the bridge between technical skill and creative expression. By practising them regularly, mindfully, and in varied ways, you build the strongest foundation for your entire musical journey at the piano. So don’t be afraid of them – see them as your best friends on the path to becoming a confident pianist.

Definitely the C major scale. Since it uses only white keys, you can fully concentrate on the correct fingering and an even touch, without being distracted by black keys. After that, the parallel A minor scale is the next logical step.

Correct fingering is the key to fluent, fast, and relaxed playing. It has been optimised over centuries to give your hand the most efficient movement across the keys. If you learn the correct fingering from the very start, you avoid bad habits that can slow you down later and are difficult to correct.

In the long run, the goal is to feel comfortable in all major and minor scales. But in the beginning, it is more than enough to focus on those with few accidentals (up to three sharps or flats). The rest will come with time and with the pieces you learn.

Consistency is more important than length. It’s better to set aside 5–10 minutes every day for scale exercises than to practise for an hour once a week. This way you build muscle memory in your fingers most effectively and make faster progress.

Always begin with each hand separately. Focus fully on the right hand first until the sequence and fingering are secure. Then do the same with the left hand. Only when both hands can play the scale perfectly on their own should you start combining them slowly. This step-by-step approach prevents overload and leads to cleaner results.

Blues is the root of almost all modern music and has produced countless legendary tracks that became immortal on six strings and 88 keys. In this article, we present 10 unforgettable blues and blues‑rock songs every musician should know.

Anyone can learn piano – all you need is the right method, a bit of patience, and a love of music. This guide will take you through the most important basics, from the keyboard layout to note values, time signatures, and your first melodies and chords. With simple exercises and practical tips, you'll quickly see progress – perfect for beginners!

Looking for the best piano learning app? We compare the top apps for learning piano online – flexible, personalised, and available anytime ✓